Frank Molloy tells the story of the first major WWII bombing raid on Greater London, and asks if it really was a case of mistaken identity, as historically maintained. Part 3 of 3.

As noted in the introduction to part one, the Croydon Airport raid by the Luftwaffe 210 Group on August 15th 1940, seems to have been somewhat airbrushed out of history. This is puzzling. Especially when you consider its impact: the first major aerial bombing attack on the wider London metropolitan area, the significant loss of life, the serious casualty figures, the major damage and destruction it wrought on infrastructure, and the high ratio of German aircraft losses. Indeed, it was a calamitous event for both sides.

That the raid’s significance is often downplayed appears to be the result of the claim that Group Commander Walter Rubensdörffer’s 210 Group had ‘mistaken Croydon for Kenley’. Therefore, Croydon was incorrectly bombed, not deliberately. The general story goes that the formation were unexpectedly diverted near Sevenoaks, and that by the time they had regrouped, they had to adjust to new bearings, were flying into the sun, and the airfield that (handily) loomed in the distance was Croydon. One of the pilots apparently called out over the radio that base had reported the wrong target was being attacked, and that they were to pull out, but the reply was ‘Wir greifen schon an‘ (’We are already attacking’). Thus, we are presented with a fait accompli arising from a simple case of ‘mistaken identity’.

There is a connection here with the ‘Accidental Blitz’ narrative. For years, it has been commonly accepted that the full-scale bombing of London derived from an incident when a couple of Luftwaffe bombers unintentionally veered off course and dropped their payload on the capital city on the night of Aug 24th 1940. Historians have recently challenged this theory based on evidence from the diary of Hitler’s propaganda minister Josef Goebbels.

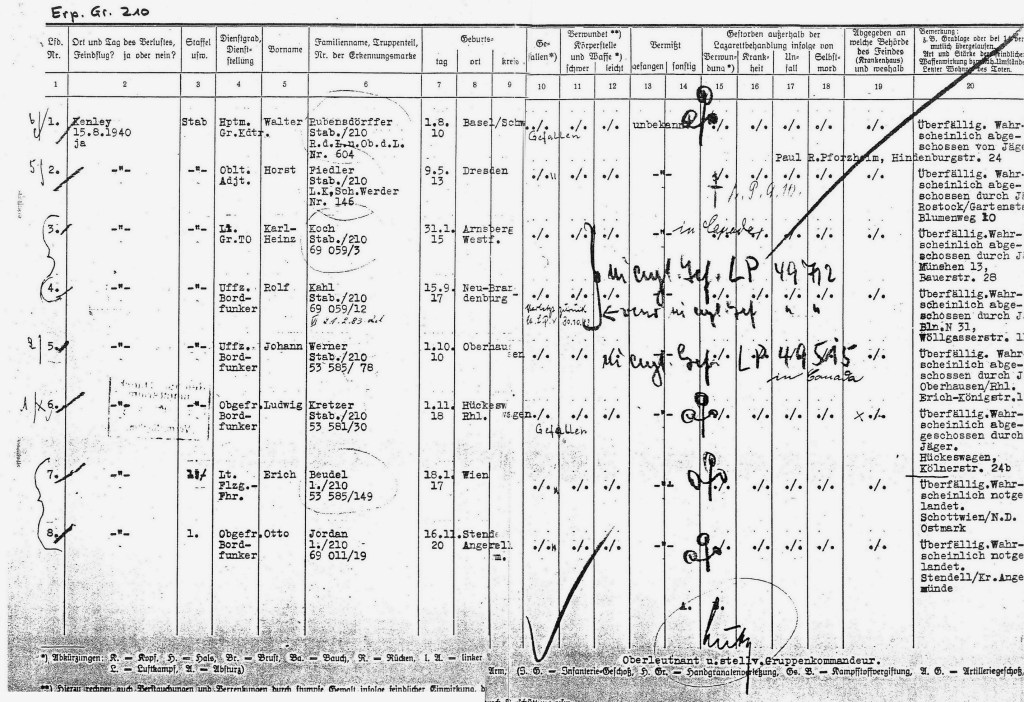

Much of the evidence for the Croydon ‘mistake’ is based on information supplied by the Luftwaffe. To a certain extent we are rather reliant on their version of events. Of course, in the wider field of historic interpretation, we should be wary of such material. Even with contemporary documented records, although they are a valuable primary source, they are not always 100% accurate. They often contain errors, gaps or omissions in dates and targets, frequent mis-identifications of aircraft, and mis-calculations in numbers. Sometimes details of entire missions are left out. Indeed, only two of the five missions that 210 Group undertook on August 15th are properly logged. Nonetheless, in this particular mission there is a key document that cannot be dismissed: the Namentliche Verlustmeldungen. This is the personnel loss report submitted up the line from unit level after a mission. The hand-written entry for August 15th clearly states that 210 Group were tasked to attack Kenley.

However, even if we concede that Kenley was indeed the ‘official’ primary target, the circumstances for ‘mistakenly’ bombing Croydon remain problematic. Some of Group Commander Rubensdörffer’s decisions point to an ulterior motive and his intentions are certainly open to speculation. Employing an aggregated timeline of events collated from the various historiographies, the following examines the questionable aspects of a mission described as one of the most controversial raids of the Battle of Britain.

Dornier Distraction

Firstly, is it any coincidence that the bombing raid on RAF West Malling just before the attack on Croydon has also been labelled as ‘mistaken’? Several sources say that the Dornier group that flew in ahead of 210 Group initially appeared as if they were heading towards Biggin Hill. But somewhere on the approach they were met by an RAF welcome party and diverted north-eastwards to attack West Malling. This presents us with an alternative scenario. On engagement, had the Dorniers diverted further north-west they would have drawn the full wrath of RAF squadrons to the Croydon/Kenley area, jeopardising any precisely orchestrated bombing mission 210 Group had planned. But by diverting north-eastwards to attack RAF West Malling just a few miles away, they could draw the ire of RAF resources, freeing the airspace for the incoming 210 formation. There are previous examples of such tactics. The Luftwaffe raid on Dover on August 14th, which strategically achieved very little, has been cited by two sources as a diversion to allow 210 Group a low and initially unnoticed bombing run on RAF Manston. Similarly, the same day’s successful raid on Martlesham Heath was achieved after another bomber group enticed 17 Squadron’s Hurricanes out to sea. So was the Dornier mission on Biggin Hill similarly a feint? Equally, was this relatively simple ‘diversion’ masking what was to be the original Dornier group target anyway?

Flights of Fancy

Next, we have the vexed question of what happened to 210 Group’s fighter escort wing. In general, these units were tasked with shielding the bomber group from hostile attacks. In the event of an interception, they were to engage enemy fighters with the objective of drawing fire away from the bombing group, allowing them to execute their mission unhindered. Time and distance were limited. The main Luftwaffe fighter plane, the Messerschmitt Bf109, had a range radius of about 125-miles. From the airfields on the French coast, they could just about reach central London. There was little scope for time-consuming shenanigans.

The support for 210 Group that day was meant to have been provided by a flight of Messerschmitt Bf109E’s from the JG52 Group. But as 210 Group rose in altitude in the Bexleyheath area for their bombing mission, their escort was absent.

John Vasco in Bombsights Over England (1990), a study of Erprobungsgruppe 210 in the Battle of Britain, remarks that the reason for the escort leaving the bomber party has never been satisfactorily explained. They flew about 600 feet above the bombing formation as they made their way in from the coast but then they became detached, returned to base and took no further part in the action. He also observes that the absence of the escort proved crucial and contributed to the Croydon “debacle“.

Christer Bergström in Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited (2015), states that the fighters of JG52 were “demoralised” due to previous losses, and suggests a lack of confidence accounted for their sudden desertion over southern England. Dilip Sarkar in Attack of the Eagles (2024), offers the narrative that they “lost their charges owing to haze flying into the setting sun“. In which case, the escort provided a chaperone all the way in from the coast, remained with 210 Group following the change of direction, carried on with them up to the sharp south-westerly turn, and maintained their presence for a short while as the whole formation headed towards the sunset. While this scenario is a possibility, it would mean that the escort was knowingly compromising itself on range.

Other sources suggest that the escort got waylaid by an interception of the RAF as they flew in over the coast. Between 6:30pm and 6:45pm, 501 and 266 squadrons engaged with large forces of Bf109s between Dover and Dungeness, and the JG52 Group may have been drawn into this. Perhaps they simply went off hunting on their own. Luftwaffe fighter escorts often abandoned bomber parties to do this. It was one of Göring’s main complaints to his fighter-commanders. Francis Mason in Battle Over Britain (1969), claims that 210 Group had no escort to begin with, as they missed their rendezvous after taking off in France.

With so many speculative theories, there is surely room for another. Which is that as 210 Group diverted over Sevenoaks and began rising in altitude, the fighter escort recognised that this was a significant and unplanned change in tactics. In this case, they couldn’t afford to join their charges as it might have meant exceeding their range. Thus, as cited by 210 Group Technical Officer Lieutenant Karl-Heinz Koch, the reason for their withdrawal was concern about “a shortage of fuel”. With the knowledge that the Bf109’s in the bombing formation could at least offer some protection, the fighters simply left 210 Group to complete their mission. Was this just as Rubensdörffer expected? Richard Collier indicates in Eagle Day – Battle of Britain (1996) that the commander was rather matter-of-fact in acknowledging the sudden loss of escort. His radio message “The fighter protection has withdrawn.” was delivered in a voice tellingly “shorn of reproach or bitterness”.

Right Course of Action?

If Kenley was the intended target, the most direct flight route from the Kent coast at Romney was along a north-westerly line, hugging the eastern contours of the High Weald, with a westerly climb to altitude when reaching the North Downs. The advantages of 210 Group using this approach were evident. They would have had the sun in their favour, probably held onto their fighter escort, finished the job half-an-hour earlier, and maybe had an easier ride back. So it remains puzzling why 210 Group, as Richard Collier put it, “mysteriously altered course”. Could it be that if Kenley was a feint, and Croydon was the intended target, Rubensdörffer was keen to avoid a trap? Attacking from the south-east there was a manifest risk of getting caught in the perilous core of a triangular web of RAF bases, Biggin Hill, Kenley and Croydon. Likewise, by banking further to the west to attack Croydon from the south would have meant being squeezed between the RAF bases of Redhill, Kenley and Croydon.

Francis Mason believes that 210 Group were daunted by their complete lack of fighter protection, and were therefore “hoping to confuse the defences” of the RAF by sweeping north in order to attack Kenley from another direction. But there was a substantially greater risk in “hoping” than using the simpler option. From the moment they deviated from their original trajectory in attacking from the north-east, they added on twice the distance to the target. They lost precious time and precious fuel whilst retaining a payload that sapped both. They also risked losing fighter protection, formation and bearings, as well as jeopardising safety and missing the initial target (!) by flying into the sun. Why take such a last-minute gamble? Unless, of course, a ‘Plan B’ was pre-conceived.

Perhaps 210 Group had actually come under attack somewhere near Sevenoaks and were forced to deviate from their original plan. There is no evidence of this, but if it was the case, you might reasonably expect a more panicked mission, borne from a desperate revaluation of the pressurised situation they found themselves in. Not least, the launching of a renewed attack using an unplanned realigned trajectory while flying into the sun.

Cool, Calm, Collected

Far from the scenario of a haphazard, uncoordinated attack, the raid on Croydon points to a Luftwaffe force implementing a methodical, orchestrated and disciplined raid, following the tactics that Rubensdörffer devised himself, diving at the prescribed 45 degrees and pulling up after the bombs had been dispatched. They appeared confident in their textbook manoeuvres and relatively indifferent to RAF attack. In a letter to John Vasco, 32 Group Squadron Leader John Worrall, later Air Vice Marshal, writes that his flight arrived to find the attackers “stooging around in a bombing circle in a leisurely manner. These dived in turn to drop bombs on Croydon Airport. They seemed not to notice us because return fire from their gunners was sporadic.” He adds, “The Me 110s and 109s (210 Group) present above the bombing circle paid no attention to the RAF fighters, which was unusual.” 210 Group did not all go in to attack at the same time. The four different squadron elements patiently waited their turn in the queue to go in and bomb the airfield. Vasco quotes Otto Hintze, Captain of the Bf109 fighter-bombers of third squadron, who stated that the elements were “selectively dive-bombing in turn.” Hintze also recalled how his unit was the last to go in, and as they climbed for height, there was more difficulty getting into the correct formation, as by this time the RAF fighters had begun to engage with them.

Play Misty For Me

Another excuse for the ‘mistaken identity’ is that once 210 Group had changed tack, they were flying into the haze of a low setting sun, and again, although their target was still Kenley, they were blindsided into attacking Croydon. 210 Group crew members hint at this justification. We have Rubensdörffer’s comment “Are we over land or sea?”, and Lieutenant Hintze later mentioning a “mist” at high altitude. Lieutenant Koch blamed sight impairment in excusing Rubensdörffer for the attack. He stated, “In the target area we encountered a rather poor vertical visibility due to haze caused by the declining sun. Because of this, our lead missed the target and we attacked Croydon airfield instead of Kenley airfield.” The “lead” was Rubensdörffer. Koch continues: “When somebody called over the radio to break off, it was too late since it was shortly before bomb release. I personally realised during the dive that it must be the wrong target, however I, as No.3, had to follow No.1 and No.2.”

But was it all just a smokescreen? Had the Germans conjured up a scotch mist in south London for the history books? Atmospheric haze is a scattering of light usually caused by the sun reflecting fine suspended particles of dust or water droplets. Like looking through a filter, it can cause glare, diminish clarity and contrast, reduce overall visibility and make it harder to discern or identify landmarks or terrain. But the impact is generally on the perception of distance and depth, not direction. For an experienced crew, an evening summer haze would not be an unexpected meteorological event. The RAF pilots didn’t seem to have been as disorientated with it. And although Lieutenant Hintze mentioned a mist, he perhaps tellingly pruned it as a key factor, by casting it only as a “maybe”.

The sun’s position is fundamental to flight training and underlies the basic rules for pilot combat manuals. Even allowing for glare impairing their ability to read their navigational instruments, the position of the sun would have provided 210 Group with an accurate clue as to their whereabouts. If the target was Kenley, then around about the time when 210 Group commenced its bombing run from Bexleyheath, the setting sun would have been at 270° true west. That would have been 45° to the west of their incoming trajectory and 70° west of the line of the runway. The bombing run at Kenley would have had to have started a good three hours earlier for the sun to have been immediately in front of them.

At Kenley (left), the sun is out of shot being 70° to the west of the runway. At Croydon (right), the sun is clearly in line of vision.

In addition, from Bexleyheath, Croydon was not on the same linear route as Kenley. There was a substantial difference in the navigational bearings of about 15°. Because of this, the sun was in the line of vision for Croydon. 32 Squadron pilot Humphrey Russell had worked this out on his approach from Biggin Hill. He noted, “The sun was already low in the west. I realised that the Germans would be flying directly into it and I didn’t envy them.” The sun as a simple navigational aid would have given 210 Group clear prior warning that they flying in the wrong direction for Kenley, or the right direction for Croydon. And even in the unlikely scenario of complete misjudgement of the sun’s position, then what a convenient outcome that the error led Group 210, not down a blind alley, but precisely to a primary alternative target. Fortune, indeed, is doing some heavy lifting.

At Kenley (left), the sun is over the western perimeter fence. At Croydon (right), the sun is directly over the airport buildings.

Plain as Day

Topographically speaking, it’s also a bit of a stretch to imagine the Luftwaffe could mistake Croydon for Kenley from the air in 1940. The bare pear-shaped Kenley airfield is elevated 560ft above sea-level, and keenly surrounded by wooded hillside. The runway has a north-south orientation. Apart from hangars and workshops, there were no surrounding aviation or associated industrial buildings. By contrast, Croydon aerodrome, which sat in the valley of the river Wandle, was nearly twice the size in area, linking a southern ring of London suburbs. The runway had an east-west orientation. Aside from the control tower, hangars and other associated buildings that you would expect at London’s main airport, there was an open-air swimming lido in the playing fields opposite. It was closed, but wasn’t covered, and had a decidedly visible newly-built high-diving board. They were still clearing up here after a huge Air Raid Precautions drill on the evening before. There had been a large crowd of onlookers for the exercise which simulated the emergency response to an enemy bomber attack. Little did the ARP wardens realise how soon they would be putting what they had learned into practice. Next to this was the Waddon waterworks which led to the Waddon housing estate with its striking circular and oval street designs. More enticingly, a huge industrial plant lay just to the north-west of the airport. It included the Croydon ‘A’ power station, with its soaring wooden cooling towers, Beddington water-treatment works, the gasworks, and hundreds of production plants along Factory Lane and Imperial Way. Snaking through this landscape as a visual guideline was the four-lane wide A23 bypass which was built in 1924. On top of all that, 210 Group’s attack trajectory would have taken the formation right across the built-up conurbation of the town centre. From the air, in daylight, sun, mist, or not, surely the approach to Croydon, even from a distance, was unmistakable?

Civil War

As civil aviation crew members before the war, some of the 210 Group would have been familiar with using Croydon as London’s main peacetime airport. By 1938, Lufthansa flights to Croydon were regularly carrying Luftwaffe pilots as co-pilots to share navigational experience. It was also noted that some German pilots coming in and out of Croydon were taking slight detours in order to map out more thoroughly the lay of the land. According to a contemporary newspaper report, “German civil-cum-military pilots flew all over Europe daily on the services of the German air lines. The old three-engine Ju52 passenger aeroplane flew in and out of Croydon Airport for years.” Following the attack, the Air Correspondent for the Sunday Dispatch wrote. “Two of the German airmen who took part in last week’s raid on Croydon Airport were civilian pilots for the German Lufthansa airline. They were shot down and are now prisoners. They were quickly recognised. Before the war, they flew to Croydon from Cologne every other day.”

Certainly, the pilots of 210 Group didn’t just jump into the cockpit and fly blind over England. Missions were thoroughly calculated beforehand. They would have spent hours poring over maps and reconnaissance photographs, studying topological models and examining landmarks. Indeed, on the very morning of August 15th, a Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft crossed the Sussex coast and flew over the Kenley and Croydon airfields, returning without being intercepted. Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief Göring revealed that his special crews made intensive studies of targets, studied meteorological conditions, examined navigational solutions and planned suitable methods of attack. In short, they did their homework.

Industrial Precision

The spectacular feat of targeting Croydon’s surrounding aviation industry with such devastating accuracy must also be taken into consideration. Workshops, factories and engineering works near to the aerodrome were precisely hit, despite the fact that they were camouflaged to appear as a country scene from the air. It was in these areas that the death toll was highest. By the time 32 Squadron had arrived on the scene, 210 Group had already completed the bombing of Croydon airfield and its surrounding infrastructure, and were ready to disperse. The Luftwaffe had already targeted such strategic inland sites with similarly swift precision raids. The attacks on the aircraft factories of Boulton Paul in Norwich, Supermarine in Castle Bromwich and Short Brothers in Belfast are testament to that. But given the unorthodox approach, the Croydon raid was one of the most effective inland assaults yet (as was, incidentally, the earlier West Malling raid by the Dorniers). What a convenient outcome of this last-minute extracurricular mission. Again, more heavy lifting for fortune.

One of the factories that was savagely targeted was British NSF on the Queensway industrial estate, a good half-mile away from the airstrip. With a workforce of about 300, the company produced a range of vital electro-mechanical and technical aircraft components. It was originally a subsidiary of a German firm, the Nuremburg Screw Factory (NSF). However, in 1939, the company was taken over by the British government, and the German members of the senior management team returned to their homeland on the outbreak of war. They would have taken with them a considerably detailed knowledge of the factory’s position as well as the locations of all the nearby aircraft manufacturers and servicers, such as Redwing and Rollasons, which were also destroyed on August 15th. Surviving employees maintain that British NSF came under such sustained and concentrated bombing that it completely obliterated the entire factory. The scent-making Bourjois factory next door was essentially destroyed by the impact of the explosions. A subsequent British NSF company report made it clear that far from the notion that the raid was a mistake on the part of the German pilots, it was in fact, intentional and calculated.

On Closer Inspection

Local accounts often provide a sharper lens with which to focus on historical events. Croydon’s chief librarian William Berwick Sayers, who was injured while serving as a Civil Defence Volunteer, published Croydon and the Second World War, the borough’s official history in 1949. Noting the widespread destruction of August 15th, he was unequivocal: “Croydon aerodrome had clearly been the intended target.” Another detailed narrative of August 15th from a ground perspective can be found in Croydon Airport and the Battle of Britain. Here, the authors maintain that it is difficult to imagine how such an error of identification could have occurred. In particular, they also cite the precise targeting of the nearby industrial estate which was producing vital RAF equipment. As such, they draw the conclusion that the raid was likely deliberate rather than accidental.

A Government Source

Croydon Airport and the Battle of Britain also proposes a source for the origin of the ‘mistaken identity’ theory. It suggests it may have taken root in the statement made to the House of Commons by Home Secretary Sir John Anderson on August 20th, five days after the raid:

“During the afternoon of August 15th, successive waves of raiders had crossed the coast and headed towards London, but were turned away before reaching the Metropolitan area. Shortly before seven in the evening, another raid was reported to be approaching London from the same direction. A few moments later, it was reported to have turned away as the earlier raids had done. In the light of what had happened earlier in the afternoon, it appeared that the threatened attack on the London area would not materialise and Fighter Command decided to withhold the order for the sounding of the public warning. However, a portion of the enemy formation broke away from the others, changed direction suddenly, and delivered their attack on Croydon.”

Given the perilous situation the country was in, Anderson was clearly aware of the importance of maintaining public confidence and military morale on the home front. As such, he could hardly give the Luftwaffe credit for a clever diversion that bypassed all Fighter Command’s defence systems and allowed a bombing group to get within striking distance of central London. Likewise, for Fighter Command to admit to being hoodwinked (akin to falling for what Captain Mainwaring might describe as “a typical shabby Nazi trick.”) was tantamount to indicating it had no idea what the Luftwaffe was doing. The British authorities operated under the premise that the Luftwaffe was being kept at arm’s length. They had to be seen as in control, and it was important to give the impression that Fighter Command had full knowledge of the enemy’s objectives. The Government’s line was that because of this superior intel, waves of Luftwaffe attacks were being systematically repelled. So the pitch in this case was, yes, a rogue group had been monitored on its initial approach, and had also been expected to turn back, but the robust RAF defence caused this unit to mistakenly digress from the enemy pattern.

Plotting a Path

Considering their losses, this ‘mistake’ excuse would suit the Luftwaffe too. Remember Rubensdörffer’s comment “Are we over land or sea?” Was he subtly planting the seed into the minds of his subordinates that their mission was now at the mercy of the unknown? At the same time, was he preparing the groundwork for a case of mistaken identity in the event of any subsequent disciplinary hearing?

In circumstances of perceived failure, a Luftwaffe commander with any nous would be aware that the Wehrmacht hierarchy, by nature of its existence, feasted on scapegoats. And Göring, frequently furious with his commanders for repeatedly ignoring his strict orders, may also have sought a sacrificial lamb. But had Rubensdörffer survived, it is unlikely that he would have been found guilty, as is often cited, for disobeying Hitler’s orders forbidding the bombing of London targets. True, in 1940, Croydon was not technically part of London (and wouldn’t be until 1965), but aside from the airport operating under the name London Airport, it also came under the scope of the wartime London Civil Defence Region. This body comprised nine subdivisions which included the 28 metropolitan boroughs plus the City of London, East and West Ham, and Croydon, which made up the final ninth subdivision.

In any case, on August 1st, Hitler had himself issued a directive extending Luftwaffe operations to the RAF-related industries. Not only did Croydon fit the bill, but it had already been officially targeted for attack on August 13th or Adlertag (Eagle Day), the start date for the Luftwaffe campaign on Britain. However, this mission by bomber wing KG54 was cancelled owing to bad weather. Rubensdörffer’s greatest likelihood of receiving a guilty verdict in a court-martial would have been if he had openly admitted to a risky diversionary attack on an unscheduled target, in which 15 other experienced officers and airmen were either killed, wounded or captured, and a quarter of the planes under his command lost.

Walter’s Way

In my opinion, 210 Group Commander Walter Rubensdörffer knew exactly what he was going for on the evening of August 15th 1940. Kenley may have been the official target, but it was already in his mind to bypass it. He was in no doubt that his 210 Group could knock out the principal enemy airport while wreaking crippling destruction on the surrounding aviation industry and infrastructure. He knew the route he would take, accounted for the extra risks, the lack of a fighter escort and the setting sun. His decision might also nullify the enemy’s warning systems, reinforcing the element of surprise. He believed he could execute his plan to devastating effect, employing diversionary tactics, textbook procedures and ready-made excuses.

Rubensdörffer’s confidence may have been rooted in the Luftwaffe’s appraisal of Croydon’s strategic significance. From the very beginning of the Operation Sealion offensive, Croydon was living on borrowed time. As mentioned, it had already officially been singled out for attack on August 13th. But the key directive for a sanctioned surrogate attack on Croydon came on the very morning of August 15th, when Göring summoned his chief commanders to his country estate HQ at Karinhall, then proceeded to issue a series of decrees. For Rubensdörffer, it might have been manna from heaven. One order clearly referred to the enemy aircraft industry as a legitimate alternative target of strategic importance. Another directive gave his 210 Force a specific allowance: “Such sorties are to be undertaken only by specially selected crews who have made a prolonged and intensive study of the target the most suitable method of attack and the particular navigational problems involved.” And the instruction that twin-engine fighters (such as the BF110) could be employed in circumstances where the range of single engine escorts was exceeded, gave 210 Group a further green light. Added together, this made Croydon a perfect primary quarry.

Compared to other bomber units, 210 Group had had a successful day’s hunting on August 15th. Confidence was high, and as this was the last raid of the day, it’s possible that Rubensdörffer wanted to finish with a flourish. Emboldened by Göring’s directives, he had been granted a shot at glory. The opportunity to deliver, in literally one fell swoop, a serious blow to the enemy. A blow that would leave them reeling. Weaken them. Demoralise them. Break their fortitude. Crush their spirit. At the same time, delivering a morale-boosting triumph to the Wehrmacht, paving the way for a successful invasion of Britain. He may have not shared this decision directly with his cohorts, but knowing he had carte blanche, or at least the tacit approval of the Luftwaffe High Command, he had the self-assurance, perhaps the arrogance, to reach for the skies.

Of course, there is always another possibility: that Rubensdörffer saw himself as something of a maverick, and deliberately broke the rules in a vain and foolhardy attempt to prove the effectiveness of his beloved dive-bombing squad. Ultimately, in the words of John Vasco, 210 Group dived towards Croydon: “for a reason known only to Rubensdörffer.” But one thing we can be sure of: on that fateful summer’s evening it cost him his life, the lives of many of his cohorts, and the lives of many innocent others.

Sources

Books

Bergström, Christer. Battle of Britain: An Epic Conflict Revisited. Casemate, 2015.

Berwick Sayers, W.C. Croydon and the Second World War. Roffey & Clark, 1949.

Cluett, Douglas; Bogle, Joanna; Learmonth, Bob. Croydon Airport and the Battle for Britain. London Borough of Sutton, 1984.

Collier, Basil. Defence of the United Kingdom: History of the Second World War. Naval & Military Press. 2009.

Collier, Richard. Eagle Day-Battle of Britain. Hodder & Staughton, 1996.

Goss, Chris; Cornwell, Peter; Rauchbach, Bernd. Luftwaffe Fighter-Bombers Over Britain. Stackpole, 2010.

Jackson, Robert. Hit & Run: Daring Air Attacks in World War II. Leo Cooper, 2004.

Kaplan, Philip, & Collier, Richard. The Few. Greenwich Editions, 1998.

Mason, Francis. Battle Over Britain. McWhirter Twins, 1969; 1990.

Newton, Denis. A Few of the Few. Australian War Memorial, 1990.

Sarkar, Dilip. Attack of the Eagles. Air World, 2024.

Vasco, John. Bombsights Over England: Erprobungsgruppe 210. JAC Publications, 1990, and Schiffer edition, 2012.

Vasco, John, & Cornwell, Peter. Zerstörer, the Messerschmitt 110 and its unit in 1940. JAC Publications, 1995.

Wood, Derek, & Dempster, Derek. The Narrow Margin, Pen & Sword Military Classics, 1961; 2010.

British Newspaper Archives

Croydon Times, Saturday July 20th 1940.

Daily Herald, Monday July 12th 1940.

Daily Herald, Friday August 16th 1940.

Daily Mirror, Friday August 16th 1940.

Daily News (London), Tuesday July 16th 1940.

Daily News (London), Friday August 16th 1940.

Daily News (London), Saturday August 17th 1940.

Daily News (London), Monday August 19th 1940.

South-Western Star, Friday August 16th 1940.

Weekly Dispatch (London), Sunday August 18th 1940.

National Archive Records RAF Combat Reports

Pain: 32 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/16/18.

Wlasnowalski: 32 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/16/29.

Lawrence: 54 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/21/47.

Hopkins: 54 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/21/42.

Robbins: 54 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/21/63.

McNab: 111 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/43/5.

Thompson: 111 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/43/6.

Wallace: 111 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/43/91.

Corfe: 610 Squadron. August 15th 1940. Ref: AIR 50/172/12.

Websites

https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/177240

https://www.battleofbritain1940.net

https://battleofbritain1940.com/entry/thursday-15-august-1940/

https://community.netweather.tv/topic/63129-the-battle-of-britain-weather-diary/page/4/

https://www.historynet.com/no-the-london-blitz-wasnt-started-by-accident/

https://www.historiccroydonairport.org.uk/history/world-war-ii-military-operations/

https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/UN/UK/UK-Defence-UK/UK-DefenseOfUK-12.html

https://www.key.aero/article/croydon-airport https://keepituryens.wordpress.com/2016/08/15/

https://www.keymilitary.com/article/croydon-raid

https://www.volksbund.de/

https://www.warstateandsociety.com (casualty figures).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanalkampf