Frank Molloy tells the story of the first major WWII bombing raid on Greater London, and asks if it really was a case of mistaken identity, as historically maintained. Part 1 of 3.

In the summer of 1940, German forces prepared to put into action ‘Operation Sealion’, a full-scale invasion of Britain. As a prelude, the German air force (Luftwaffe) planned to knock out the entire British air defence system with the objective of taking command of the skies. The resultant clash became known as the Battle of Britain.

In the early weeks of the hostilities, because of the strategic importance of ports and docklands, it was mainly coastal areas that were targeted by the Luftwaffe. But some inland locations also became the focus of their attention, and one of them was the south London suburb of Croydon.

Croydon was a fairly built-up urban district in 1940. It had an area of about 20 square miles and an estimated population of 214,000. This was down from the pre-war population of around a quarter of a million owing to evacuations. However, the town could draw on many visitors. Its shopping centre, the largest in Greater London outside the West End, boasted three major department stores, Allders, Grants and Kennards. There was also a vibrant evening entertainment culture with plenty of pubs, theatres, cinemas and restaurants.

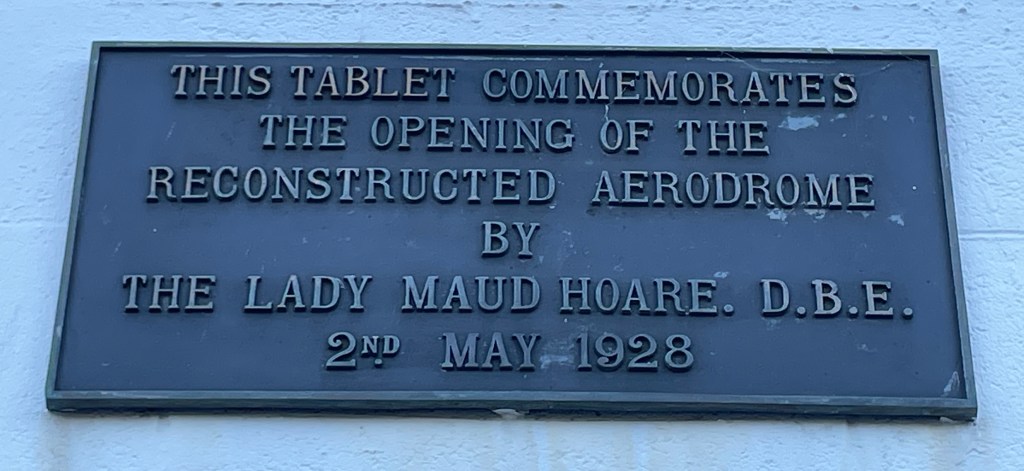

But Croydon was more renowned as the location of London’s main international airport. It had opened in 1920 as the world’s first purpose-built civilian aerodrome, with later innovations including the first custom-made control tower, terminal and hotel. The aerodrome was globally famous. Newsreels captured the occasions when VIPs graced the tarmac. Stars of the silver screen, such as Douglas Fairbanks Jr, Mary Pickford and Rita Hayworth touched down on glitzy visits to London. There were grand appearances at air-shows from aviation pioneers such as Charles Lindbergh and Amy Johnson. And politicians arrived and departed on important matters of state. Indeed, the Prime Minister Sir Neville Chamberlain landed here on August 26th 1939, with the final phoney assurances from Adolf Hitler.

The outbreak of war a week later effectively signalled the end of the airport’s heyday. But Croydon remained a core military target. Primarily, because of its global prominence, Croydon’s destruction would have been a major propaganda coup. As early as October 1939, it had been singled out. Radio broadcaster William Joyce, posing as the Nazi propagandist ‘Lord Haw Haw’ attested to the airport’s key position in the protection of Britain when he delivered a grim warning to listeners: “Croydon must be aware she is the second line of defence… We shall bomb it and bomb it to a finish. We advise people there to evacuate the area… as we shall do the job thoroughly.”

Another major reason for its targeting was that although its entire civilian airline business had been relocated on the outbreak of war, several key aviation factories remained active in an industrial plant adjacent to the airport’s western administrative blocks. There were about 20 in all, comprising aircraft manufacturers, mechanical engineering works and technical component units.

Croydon was also strategically significant from a geographical aspect. Two pivotal RAF stations had already been established in close vicinity: Kenley, three miles away and Biggin Hill, six. Now, under the command of Kenley, Croydon became home to a new RAF fighter base, providing London’s very last line of aerial defence.

As a major objective for the Luftwaffe, Croydon had a baptism of fire on August 15th 1940, becoming the victim of the first major WWII bombing raid on Greater London. Yet few history books or documentaries mention this attack, and if they do, it’s only in passing. In The Narrow Margin, one of the seminal histories of the Battle of Britain, the description of the raid is almost dismissive: “Other bombers wandering over Surrey decided to deliver their loads on Croydon.” In some instances, the attack is even ignored. In 2020, Channel 5 ran a three-part series entitled Battle of Britain – Three Days that Saved the Nation. The first episode was all about August 15th. It was generally well presented with plenty of contributions from history experts. However, the programme rather abruptly concluded with the bombing raid on Portland at 6:20pm, with the inference that it was the last of the day. However, it was precisely at that time that a bomber formation had taken off to launch August 15th’s final and most devastating attack on England, and it would be led by one of the Luftwaffe’s most celebrated and distinguished flying aces.

Group Commander Walter Rubensdörffer was 30 years of age. Born in Switzerland, he was an experienced pilot who had learned how to fly bi-planes as a teenager. He was respected in the Luftwaffe as a decorated veteran of the Spanish Civil War, where he flew with the German Condor Legion.

On July 1st, 1940, he was put in command of Erprobungsgruppe 210. This was a specially formed wing of experienced combat pilots. They were originally tasked to be the operational test unit for the new Messerschmitt 210 bomber. Leading German aviation experts were drafted in to supervise the training. However, trial results were not positive. Instead, the group was switched to practice precision dive-bombing attacks using a combination of converted Messerschmitt Bf109s and Bf110s. The initials Bf stood for Bayerische flugzeugwerke (Bavarian aircraft-works).

The Bf109 was single-engine, single-seater fighter with a speed of up to 340mph. Most were equipped with variable combinations of cannon and machine guns. A new fighter-bomber version trialled by 210 Group was equipped with a high-altitude engine and a rack carrying one 550lb bomb or four 110lb bombs.

The Bf110 Zerstörer (destroyer) was a twin-engine, two-seater heavy fighter-bomber with a similar speed. Most were equipped with two 550lb bombs, two cannon and four machine guns. A new version trialled by 210 Group carried a single more powerful 30mm cannon. On its own, the Bf110 could operate as an attacking escort aircraft, but it was comparatively disappointing in this role. It was more bomber than fighter.

A Luftwaffe bomber wing was typically made up of three squadrons (staffeln) of nine to twelve aircraft, divided into ‘swarms’ of four to six aircraft, and sometimes divided into ‘chains’ of three aircraft. 210 Group was made up of ten Bf109s and 18 Bf110s divided into a staff flight, three squadrons, and an army of ground personnel. They were based at Denain in the French interior, 80 miles south-east of Calais.

Rubensdörffer’s task was to develop live ground-attack combat strategies for the fighter-bomber. He devised the tactics himself. His prescribed method was a low-level sea and terrain-hugging technique, as radar was less effective below 1,000ft; next, a climb to an altitude of at least 9,000ft; then, a fast but shallow 45-degree dive, pulling out at 1,000ft and releasing the payload. The success of these raids also relied on other Luftwaffe units providing distractions, diversions and feints to allow 210 Group an undisturbed bombing run that would be as devastating as possible.

Luftwaffe General Albert Kesselring cherished 210 Group above all other units, but he was sceptical of their accuracy. Rubensdörffer was determined to prove him wrong. From July 13th to 30th 1940, Rubensdörffer’s fledgling force practised their techniques on the British sea traffic in the English Channel. They claimed remarkable results, sinking around 90,000 tons of shipping including a number of warships. Kesselring personally congratulated them.

Raids on shipping continued during the first days of August, before 210 Group was switched to land targets. On the morning of the 12th, they were honoured with the task of knocking out England’s south coast radar system as a prelude to an invasion. They were now about show their worth in the precision bombing of land targets.

The mission took off from Calais with 20 aircraft divided into four squadrons. Flight Lieutenant Hintze’s Bf109s were given Dover, Captain Lutz’s Bf110s Pevensey, and Flight Lieutenant Roessiger Bf110’s Rye. Rubensdörffer’s own Bf110 flight took the inland station at Dunkirk near Canterbury. The raids were pin-point accurate, and the stations were structurally damaged. However, the radar system itself was only temporarily disrupted. Based on Rubensdörffer’s report, Kesselring made the mistake of thinking the RAF was now blind. The toll of German pilots in other actions over the next three days convinced Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief Hermann Göring otherwise, and he issued a directive banning any further radar missions as they were proving futile.

Around midday on the 12th, another mission of around 20 bombers from 210 Group mercilessly pounded RAF Manston, the first major attack on this airfield. When they left, a load of Dornier bombers turned up to give it another going over. In the early evening, 210 Group were up once again. This time with an attack on Hawkinge near Folkestone, the most forward of the RAF airfields.

The official start date for the German air attack on Britain was codenamed ‘Adlertag‘ (Eagle Day). After several false starts, August 13th 1940 took the title. The Luftwaffe mounted 1,485 sorties on the airfields of Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Hampshire. Missions for 210 Group were among them. However, low cloud severely hampered the effectiveness of many raids, while others were abruptly called off. Not exactly a false start but something of a weak one.

Attacks on the 14th were even more disrupted by the weather pattern. The Luftwaffe was reduced to less than 500 sorties, mainly confined to coastal areas. However, around midday, there was ‘a hell of a donny’ over Dover following a feint attack on Ramsgate. There were numerous dogfights at high altitude involving some 200 aircraft, including half of RAF 54 and 65 Squadrons who were using Manston. Using the diversionary melee as cover, Rubensdorffer’s crack force came in low and unnoticed to hit Manston once again. Many grounded Spitfires and Hurricanes were lost, and the station was put out of action once more. Under continued heavy bombardment, the strain had begun to tell and there was a collapse in command and discipline at the airfield. With weaker protection than usual, RAF pilots had to be drafted in to man defensive guns and to refuel and rearm their own planes. Poor Manston. Known as ‘Charlie 3’, it was the most easterly and exposed of all the airfields in the south. Unloved, except for the Luftwaffe’s infatuation.

On the morning of August 15th, the RAF were no longer favoured by the ‘typical’ British summer. The clouds dispersed to reveal clear blue skies. The real Adlertag had arrived. The Luftwaffe tried to overwhelm the RAF with a massive wave of attacks. They launched nearly 1,800 sorties. the largest force sent in a single day during the Battle of Britain.

210 Group were particularly busy, with five missions that day. At about 3pm, they went out hunting as part of a larger formation, this time in Suffolk. Part of another bomber group purposefully distracted the Hurricanes of Martlesham Heath’s 17 Squadron, luring them 20 miles out to sea. Taking advantage, 16 Bf110s of the 210 Group slipped through the net and spent five minutes bombing and strafing Martlesham in a low-level attack. They got away without loss, leaving the airfield out of action.

Rubensdörffer’s Raiders were doing their best to wrench the finest hour from Winston Churchill’s grasp. In the early evening, the fighter-destroyers and fighter-bombers of 210 Group once again ventured out on another sortie. They were about to mount the final raid of the day.

In part two, the first major WWII bombing raid on Greater London.

One thought on “The Battle of Croydon: Part 1”